When I came of age, free love, the anti-war movement, and women’s liberation simultaneously hit the streets. And they wreaked havoc behind closed doors. The advertising industry and lawmakers, male governors of body politics, means women’s issues have been always been co-opted. Yet, thanks to other women, activists, story tellers, herbalists, and clandestine crones, I learned sovereignty over my own body.

It started in the sixties when I was introduced to the secret society of liberated midwestern women. At a Love-In, for a few seconds, I was separated from my twenty-two year old husband. With the sun at her back, a braless women in a loose T-shirt and jeans handed me a mimeographed flier. Her buzzed hair bristled like an electric halo. Without a drop of make-up on her boyish face, she looked right through my Sophia Loren painted eyes. I folded the page in half and she said, “Open it. Read it, now. You need to know this.”

Satisfied with her mission when I opened the sheet, she walked to the next recipient. Half the page was a primitive illustration of female body parts. Shutting it very quickly, I waited a beat before peeking at the text, which described the intricacies of bringing one’s self to orgasm. By the time I got to the part about intercourse and men being unnecessary, even a possible hindrance in achieving this natural wonder, my head felt like it had separated from the rest of me. My husband’s firm hand placed upon my shoulder brought an end to the euphoria.

“Who was that woman,” he said, as I crammed the paper in my bag.

“Nobody.” I held the purse to my chest.

“She looks like a troublemaker. Do you know her?”

“Never saw her in my life.”

“What’d she give you?”

“Nothing.”

“Let me see it.” He pushed his thick blonde hair behind his ears and gave me one of his famous eye-darting stares.

“No, it’s BY and FOR women.”

As efficient as a detective finding a gun on a dangerous suspect, he grabbed for my bag and pulled out the paper. Initially, he did a double take at the drawing, but when he got to the meat of the information, he said, “We’re married and you’re hiding this from me?”

We had strong ideals: us against the Establishment, his identity as an artist and my role as the muse and homemaker, I had not begun to write and didn’t know myself any better than I knew him. I stared at my feet while he stood firmly planted in this new territory, waiting for a response. Risking pleasure, our marriage, and not ready to communicate, I took off for the middle of the Love-In with him a few steps behind, calling my name.

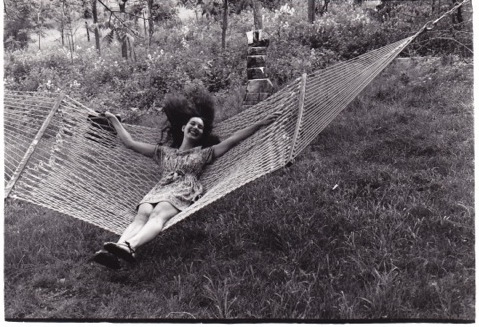

Photo credit: Larry Miller, Fluxus Artist, circa late 60’s