My mother had a thing about sweating. Even a single drop of perspiration, especially at her hairline, made her act like she was not long for this world. The unfortunate treatment of this affliction was to run around the house in a bra and cotton panties. During the heat of the summer, she dressed for her own friends, but when children came to visit, my pleadings for normal decency were met with, “I don’t give a damn. I’m not going to die for your company.”

But her sweating practices were innocent compared to what went on when she was behind the wheel of a car. Proudly driving ‘like a ‘bat out of hell,’ she was in the habit of turning to her four children as she screeched to a halt at a red light, and commanding that we “Act normal.’’. Her approaches insured that while we waited for the signal to change, all eyes in surrounding cars were on us. We were trained to sit quietly until she took off from the intersection ‘like a ruptured duck.’

We only needed a general destination: ‘to hell and gone.’ Her goal after that was to save us with dramatic exhibitions of her superior reflexes. In those near-miss moments, her rage was replaced by confidence, and what she was running from was obliterated from her radar: the total wreck that was our home life.

Originally, this short was going to be about the shock in realizing ‘Act normal’ was not what most parents said to their children, an epiphany occurring in a writing class. But in re-examining some of the car stories for this post, it struck me, for the first time, as long as we were in a car, normalcy was barely required, and only when there were witnesses.

Both images by my sister, Melanie Urdang, this one of the Occulus at Ground Zero.

Both images by my sister, Melanie Urdang, this one of the Occulus at Ground Zero.

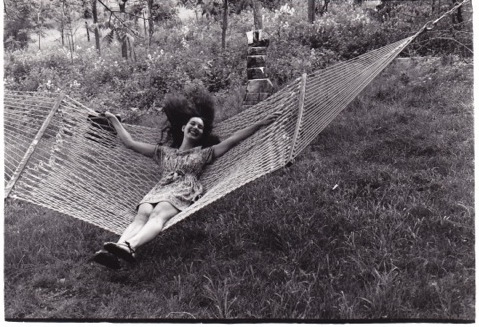

Yours truly in the third grade

Yours truly in the third grade